By Blaise Udunze

When the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) announced a new round of bank recapitalisation in March 2024, many expected the leading banks, especially those boasting record-breaking profits in the hundreds of billions and trillions, to sail through with ease. Their financial statements glistened with prosperity, with expanding balance sheets, rising dividends, and bullish share prices.

Indeed, five of Nigeria’s top 10 banks reported a combined pre-tax profit of N4.6 trillion in 2024, showing a staggering 70 percent increase from the previous year, with Zenith Bank and Guaranty Trust Holding Company crossing the trillion-naira mark for the first time. The results painted a picture of robust profitability and resilience.

Yet, barely months after the profit announcements, the same banks found themselves racing back-to-back to the capital market to raise fresh funds. By the first half of 2025, Nigeria’s banking industry was at a crossroads. Behind the glitter of trillion-naira profits lay a more sobering reality of an industry scrambling to meet the CBN’s recapitalisation directive.

The contradiction is stark: record profits on one hand, desperate fundraising on the other. If the banks were truly as profitable and resilient as they claimed, they wouldn’t be begging investors for fresh equity to meet new thresholds.

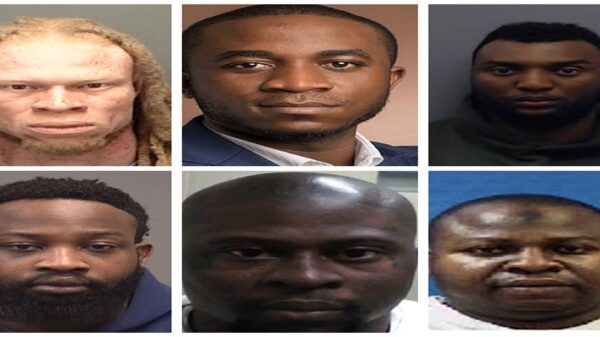

Behind the strong showing of the market leaders lies an even deeper concern. The smaller commercial and regional banks are struggling to formulate credible recapitalisation strategies. As the March 31, 2026 deadline looms, the CBN has confirmed that only 14 banks have so far scaled the recapitalisation hurdle. That leaves nearly 19 institutions still in search of capital in a market already skeptical of their true worth.

The recapitalisation push has therefore become the clearest indicator of the sector’s underlying fragility. The CBN’s new capital requirements of N500 billion for international banks, N200 billion for national banks, and N50 billion for regional banks have forced lenders to confront a fundamental question. How much of their reported profits actually represents real financial strength?

Much of Nigeria’s profit boom has been a deception, a mirage built on foreign exchange revaluation gains and arbitrary fees rather than genuine operational efficiency. The unification of exchange rates and subsequent naira depreciation in 2023 and 2024 delivered massive revaluation windfalls on dollar-denominated assets, inflating balance sheets overnight. But these were paper gains, not cash profits, and could not be deployed to strengthen capital or fund new loans.

Beyond FX gains, Nigerian banks have increasingly relied on fees and charges as easy revenue. Despite repeated CBN sanctions for breaching its Guide to Charges, banks continue to extract billions from customers through transfers, withdrawals, ATM fees, SMS alerts, and account maintenance. With over 312 million active bank accounts, these charges now contribute more to profitability than traditional lending or genuine financial intermediation.

It is little surprise, then, that the recapitalisation exercise has exposed the widening gap between declared profitability and true solvency. While five Tier-1 banks together raked in N4.6 trillion in pre-tax profit in 2024, nearly 70 percent higher than in 2023, many mid-tier banks can barely keep pace. The recapitalisation gap across the sector is now estimated at N4.7 trillion.

As of September 2025, only 14 banks had crossed the line, while others scramble for mergers, rights issues, or license downgrades to survive. The CBN’s insistence that only paid-up capital and share premium will count while excluding retained earnings has stripped away the accounting camouflage that once masked weakness.

For the market leaders, the race has been aggressive but achievable. Access Holdings raised N351 billion through a fully subscribed rights issue. Zenith Bank’s N350.4 billion hybrid offer was oversubscribed by 160 percent. Wema Bank, once a mid-tier lender, successfully raised N200 billion and became a national success story. Among specialised institutions, Greenwich Merchant Bank sealed its own recapitalisation, supported by capital injections and debt-to-equity conversions that secured its merchant banking license, while Jaiz Bank rose above the N20 billion target to remain the flagship of Islamic banking. Lotus has met the N10 billion bar, consolidating its place in Nigeria’s fast-growing alternative sector.

Another notable entrant is Globus Bank, which in 2024 raised N52.9 billion to lift its capital to N98.6 billion and followed in 2025 with a further N102 billion via rights issues and private placements. The raise subscribed entirely by existing shareholders took its capital above N200 billion. The bank now awaits final verification from the CBN before being formally recognized as compliant.

For others, however, it has been a painful crawl. Fidelity Bank’s N205.45 billion hybrid offer still leaves a N160 billion gap to the N500 billion benchmark. Guaranty Trust Bank reached its own target through a two-phased approach that started with a rights issue in Nigeria that netted N365.8 billion. Subsequently, GT listed shares on the London Stock Exchange with proceeds of $105 million to reach the required target, while UBA Plc launched a N157 billion rights issue in July 2025, following a N239 billion offer in November 2024 that was oversubscribed at N251 billion, with N240 billion accepted. The new offer, extended to September 19, 2025, helped the bank meet the CBN’s N500 billion capital requirement.

As of September 2025, First Bank has secured N187.6 billion and plans an additional N350 billion in private placements, but it still needs to secure the remaining funds to meet the CBN’s requirements. FCMB Group Plc launched a N160 billion public share offer to meet the CBN’s N500 billion capital requirements for international banks, with the offer closing on November 6, 2025. The offer follows a successful N147.5 billion share sale in 2024.

Fidelity raised N176 billion in fresh capital in 2024 and is moving to get an additional N195 billion via private placement before the end of the year. Sterling Bank has not yet completed its recapitalisation as it commenced an N87.067 public offer. This offer follows completion of a N75 billion private placement and a N28.79 billion rights issue, which was significantly oversubscribed by its shareholders.

Consolidation pressures are once again reshaping Nigeria’s banking landscape. Titan Trust’s acquisition of Union Bank and the completed Providus and Unity Bank’s merger reflect the reality that not every institution will raise sufficient equity alone. More combinations are expected in the months ahead, with smaller lenders likely to be folded into stronger franchises as the recapitalisation deadline approaches.

This trend mirrors the 2005 consolidation era, which trimmed 89 banks down to 25, ushering in a new era of scale and scrutiny. The 2024-2026 recapitalisation may well repeat history, producing fewer but sturdier players, banks large enough to finance Nigeria’s economic transformation.

But history offers a warning that recapitalisation is not reform. Bigger balance sheets may shield banks from global shocks, but they do not guarantee developmental relevance. Unless the philosophy of Nigerian banking itself changes from profit-first to purpose-driven intermediation, the sector will keep producing “giant banks in a fragile economy.”

The real challenge is not size, but substance. Nigeria doesn’t just need bigger banks; it needs better banks. It needs institutions that see SMEs as partners rather than liabilities, that lend to real producers rather than recycle deposits into government securities. It needs lenders that adopt fintech-driven underwriting, regulators that reward productive lending, and policymakers that create the infrastructure, power, and security needed to make risk-taking viable.

Recapitalisation, in this light, should not be seen merely as a regulatory hurdle but as a mirror reflecting both the success and the shame of Nigeria’s banking system. The trillion-naira profits may have dazzled investors, but the scramble for new capital reveals the truth that the sector’s foundations remain fragile, its governance inconsistent, and its contribution to real economic development still limited.

The CBN’s policy, painful as it may be, is a necessary reality check. It forces banks to prove that their wealth is more than paper-deep and that their balance sheets can support Nigeria’s ambitious $1 trillion economy vision. For investors and depositors, it is a wake-up call that what glitters in the financial statements may not always be gold.

In the end, recapitalisation is not just about raising funds; it is about restoring credibility. Because trust, once eroded by profit manipulation and corporate posturing, takes far more than a balance sheet to rebuild.

Blaise, a journalist and PR professional writes from Lagos, can be reached via: [email protected]

![]()