Pramod Mittal’s firm won a settlement tied to a Soviet-era steel plant that has sucked up more than $7 billion in Nigerian public investment without producing any metal.

Billionaire Lakshmi Mittal’s younger brother is effectively getting a helping hand — and a possible way out of financial distress — from Nigerian taxpayers, after the country’s government agreed to pay his company almost $500 million to settle a contract dispute over a deal that a previous administration said was tarnished by fraud.

Pramod Mittal, whose career in the steel industry has been less glittering than his better-known sibling — the tycoon behind the €20 billion ($21.2 billion) ArcelorMittal SA conglomerate —, has a string of abandoned factories and a trail of unpaid debts to his name. Five years ago, his Isle of Man-registered Global Steel Holdings Ltd., or GSH, was put into liquidation over $167 million owed to Moorgate Industries Ltd., a company spun off from one of the world’s biggest steel traders.

As a UK court weighed Moorgate’s request to declare Pramod personally bankrupt three years ago, the London-based Indian national held out the prospect of a payout from the Nigerian state to clear his debt. The judge was unconvinced at the time, but the settlement subsequently reached with Nigeria last year now looks like the 67-year-old’s best route out of insolvency. Still, while payments from the Nigerian government have reached GSH’s liquidators, as of Oct. 4, Moorgate had yet to see any of those funds despite having asked for them, court documents show.

With Pramod’s bankruptcy winding its way through English court rooms, a new Nigerian president has taken office, and last month his steel minister said one of the administration’s top priorities is to finally fire up the furnaces of the massive plant at the heart of the younger Mittal’s $496 million compensation. The government has justified the agreement with a former unit of Pramod’s GSH, which was announced in September 2022, saying it frees the state to pursue its ambitions for the sprawling 24,000-hectare (92 square mile) site.

The settlement — representing about 1.5% of Nigeria’s foreign reserves — is just the latest twist in the saga of the vast Soviet-built factory complex begun 44 years ago. The project has sucked up more than $7 billion in public investment and has yet to produce any metal.

The story of the Ajaokuta steel mill on the banks of the Niger River 190 kilometers south of the capital, Abuja, is often cited as emblematic of the corruption, poor governance and incompetence that bedevils the West African nation. The country’s most notorious white elephant still sparks passionate debate over whether it should be written off or revived.

“Ajaokuta has been a black hole that has gobbled up billions of dollars, enriching multiple generations of politicians and foreign enablers,” says Matthew Page, a former Nigeria expert for US intelligence agencies and now an associate fellow at London-based Chatham House. “This last failed reboot — and the giant price tag that came with it — is a preview of the next failed re-concessioning attempt. At this point, Ajaokuta’s dilapidated machinery is capable of doing only one thing: making public funds disappear.”

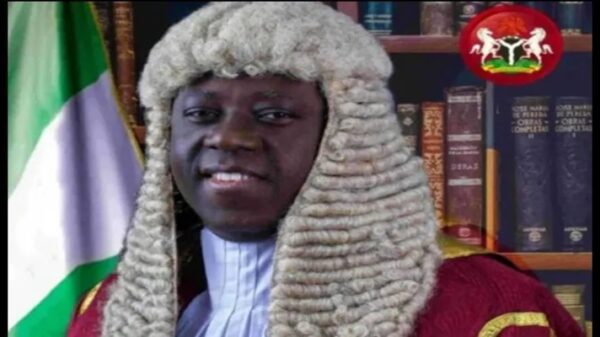

Neither Pramod’s representatives nor the spokespeople for the newly elected President Bola Tinubu and Steel Minister Shuaibu Audu responded to requests for comment. Abubakar Malami, Nigeria’s attorney general from 2015 to earlier this year, on whose watch the settlement was reached, said last year that the administration of former President Muhammadu Buhari “rescued the steel industry from interminable and complex disputes as well as saving the taxpayer from humongous damages.”

Pramod’s Involvement

Pramod entered into the Ajaokuta picture in 2004, when then President Olusegun Obasanjo awarded GSH a series of contracts, including an arrangement first to manage and later to buy the steel mill.

Shortly after GSH took over the plant, Solgas Energy Ltd., a small US company, sued it in Texas. Solgas claimed that GSH discussed becoming Solgas’ subcontractor on Ajaokuta before breaching a confidentiality accord and bribing Nigerian officials, including one of Obasanjo’s sons, to “steal the concession.” While the case was thrown out on jurisdictional grounds, in December 2008 a separate arbitration tribunal ordered Nigeria to pay Solgas $15.2 million in damages for the wrongful termination of the contract — while noting the US firm hadn’t provided evidence to support the corruption allegations.

By then, Umaru Yar’Adua had taken over as Nigeria’s president, and he canceled GSH’s contracts after a panel that his steel development minister set up said the concessions were rife with irregularities. GSH’s claim it had invested $200 million was “a ruse,” the inspectors said. Rather, the company had used its Nigerian assets to borrow more than $192 million from local banks — funds they “strongly” suspected had been dispatched abroad, they said.

The panel’s full report — never made public but seen by Bloomberg — said rescuing Ajaokuta was beyond the “financial, technical and experiential capabilities” of GSH, which instead had been “systematically cannibalizing, vandalizing and moving valuable equipment” out of the factory. GSH and its Nigerian unit initiated arbitration proceedings against the government and later entered mediation, which produced last year’s settlement.

Pramod had signed two earlier agreements with the Nigerian government – in 2014 and 2016 – that would have seen his firm retain the right to manage an idled state-owned iron ore mining company but receive no payout.

“I threatened them with criminal proceedings for tax evasion, in addition to other criminal infractions that they had clearly committed,” Mohammed Adoke, a former attorney general who had reached the first of these accords, wrote in his memoir titled “Burden of Service.” “To amicably resolve the issue, I insisted that Global Steel should relinquish (Ajaokuta) for free without any form of compensation.”

Adoke’s successor, Malami, who was the attorney general when the half-a-billion-dollar settlement was struck, modified the terms of the deal to take back the mining firm and award a payment. Malami didn’t respond to a request for comment.

Moorgate’s Case

Even before finalizing the Ajaokuta windfall, Pramod had suggested using the money to pay down the Moorgate debt. In June 2020, as Moorgate sought his bankruptcy, he told Judge Catherine Burton that GSH’s liquidators had failed to account for the “very real prospects of a payment” from Nigeria. He said his Abuja-registered subsidiary would settle the obligation to Moorgate “out of whatever money it receives from the mediation,” according to the decision issued by Burton, who — unpersuaded — ruled in favor of the creditor.

Pramod also tried another way to skirt bankruptcy — using an individual voluntary arrangement, or IVA. He proposed repaying less than £5 million out of £2.5 billion ($3.1 billion) — or 0.2% of what a handful of companies and individuals said they were owed by the businessman.

Moorgate countered that “friendly creditors” who approved this meager offer were either associated with Pramod or relying on loan agreements that were “not true or contemporaneous documents.” A UK judge revoked the IVA last November, expressing “serious doubts” about the authenticity of the paperwork. In the IVA, Pramod said he was worth £117,000, claiming he didn’t control GSH. The family’s London mansion is held through an offshore company whose directors were senior managers at GSH.

Contrary to Pramod’s argument, the court determined he controlled the British Virgin Islands-registered company that owned GSH through his influence over a family trust, with an Isle of Man judge similarly describing him as that firm’s “driving force.”

Pramod made other apparent attempts to distance himself from the group and its subsidiaries. Since April 2021, GSH’s Nigerian unit — the settlement’s beneficiary — has been owned by a Mauritian entity named Luminous Star Ltd., classified as defunct for a decade and with a director who was formerly a GSH employee. While Pramod ceased to be a director of the Nigerian firm in late 2020, his son sits on the board.

I[b]n January, Nigeria’s then Information Minister Lai Mohammed said the government had paid $446 million to GSH’s local unit in multiple instalments under the settlement. The law firm hired by the Nigerian subsidiary for the mediation made six transfers from these funds to GSH’s account, totaling £219 million ($272 million) between October 2022 and February 2023, according to reports filed by the company’s liquidators. The law firm, King & Spalding LLP, declined to comment on the rest of the money.[/b]

In December and again in March, Moorgate asked to be paid out of funds recovered by GSH’s liquidators, according to a court decision issued last month in the Isle of Man. The liquidators, who estimate that only £40 million is available for creditors once GSH’s potential tax liability and additional costs are taken into consideration, are yet to comply with the request, the judge said on Oct. 4, ruling that Moorgate is entitled to receive part-satisfaction of the debt. Moorgate and GSH’s liquidators declined to comment.

Emulating Lakshmi

Like his brother Lakshmi, who built the world’s second-largest steel producer after splitting from the family business in the mid-1990s and embarking on a legendary deal-making spree, Pramod’s efforts also hinged on international acquisitions. As Lakshmi, the UK’s sixth-richest person, entered the wealth stratosphere, his brother sought to emulate him.

In 2004, Lakshmi’s daughter got married in a lavish ceremony at Versailles, France. Nine years later, the younger Mittal spent £50 million on his daughter’s wedding in Barcelona, according to Moneylife, an Indian media outlet, and Spanish news site Vanitatis. Pramod’s spokespeople didn’t comment on the figure. Just this year, Pramod’s son got married to his long-term partner in a “multi-million-pound ceremony” at a five-star UK hotel, the Daily Mail reported.

Credit: Bloomberg

![]()