A report by Al Jazeera has documented the hidden shame of Nigerian banking system where contract staffers in financial institutions live poverty line.

Poverty wages are typical for thousands of contract workers in the banking industry and they can work for years without a raise, promotion, benefits or job security.

According to Al Jazeera, contract staffing has been a feature of Nigeria’s labour market for decades, but it is especially rife in the banking and oil sectors

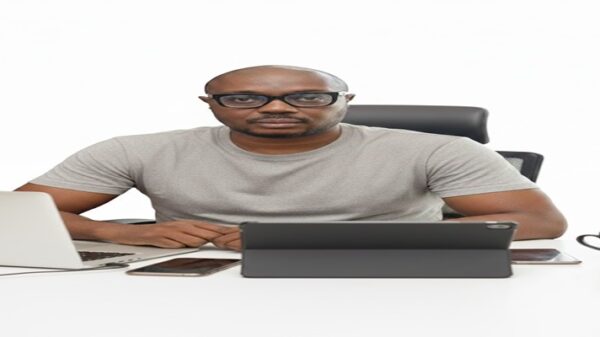

The report said that for Basit, climbing the corporate ranks of commercial banking in Nigeria has been an exercise in frustration.

The 28-year-old, whose name has been changed to protect his identity, has worked as a teller with Fidelity Bank in Nigeria since 2015.

Six years on, he is at the same branch, working at the same entry-level position, for the same meagre salary of N68,000 ($165) a month.

It is not Basit’s work ethic that is lacking, but the arrangement under which he works.

He is not technically a full-time employee of Fidelity. The entire time he’s worked there, he’s been a contract staffer hired by an employment agency he has never dealt with directly.

Being a contractor means Basit has no upward career path within the bank, or benefits such as insurance, a pension, or a severance package if he’s let go.

If Fidelity’s management is not happy with his services, or they just want to cut expenses, they can let him go when his contract comes up for renewal every two years.

In the meantime, the employment agency siphons off a portion of his pay each month as a “commission”.

Fidelity Bank did not respond to Al Jazeera’s request for comment. But Basit’s story is far from unique.

More than 42 percent of the bank workers in Nigeria were contract staffers as of the third quarter last year, reports the National Bureau of Statistics.

The remainders are full-time employees with banks – roughly a third of who are senior staffers.

Though unionists and government officials say the issues surrounding contract bank workers are being addressed, solutions have been slow to come.

And until they do, there are few employment options for the banking sector’s largely youthful contract workforce to explore.

More than 42 percent of bank workers in Nigeria were contract staffers as of the third quarter last year, reports the National Bureau of Statistics.

Profits before workers

Basit often thinks of quitting his job as a bank teller.

But there are few prospects for him in Africa’s largest economy.

Nigeria’s official unemployment rate rocketed to 33.3 percent in the final three months of last year – the highest on record and among the highest in the world.

Over half of the country’s roughly 70 million-strong labour force was either jobless at the end of last year or not working a full-time job.

That jobs deficit has made it an employer’s market, leaving workers virtually powerless to negotiate – let alone demand – better terms.

In Basit’s case, that means punishing 10-hour days that leave him little time to even explore the few opportunities which may be available to him.

‘’The challenge is that you barely have the time to go search for a job elsewhere,” he told Al Jazeera.

“You leave the house as early as 5 or 6am and you get back by 6pm or so. How do I get back as tired as this and I still start searching for job opportunities when I know that there are only few?’’

Contract staffing has been a feature of Nigeria’s labour market for decades, but it is especially rife in the banking and oil sectors.

Over half of Nigeria’s roughly 70 million-strong labour force was either jobless at the end of last year or not working a full-time job.

For Nigeria’s unionists, the so-called “casualisation” of these workers is the result of financial institutions carving out bigger profits at the expense of labour rights.

“Generally, outsourcing, as far as labour is concerned, is an exploitative system,” said Comrade Sheikh Muhammed, national general secretary for the National Union of Banks Insurance and Financial Institution Employees (NUBIFIE).

Retired bank manager Abolarian Aderemi worked in banking for more than 30 years. He says the plight of contract workers is the result of poor government oversight.

“They are exploiting Nigeria’s poor leadership,” he said. “Labour union has been kicking against it, but nobody listens.”

Muhammed says contract workers face serious hurdles to joining or forming unions where they can collectively bargain for better pay and conditions.

“[Banks] take on casual workers in order also to make sure they confuse the identity and status of the worker so that they will not be able to exercise their right of belonging to anyone,” he told Al Jazeera.

The government has established a committee to review the myriad issues surrounding contract workers in the country’s banking sector. But its efforts were disrupted by the coronavirus pandemic, Nigeria’s Minister of State for Labour and Employment, Festus Keyamo, told Al Jazeera.

“We want to review the whole issue regarding casualisation of workers with the banks and we are also in the process of reviewing all the labour laws now,” he said.

Muhammed said the review should help crack down on labour abuses.

“By the time the review is signed into a working document, no outsourcing will be done [in the banking and insurance sector] without consulting the union and taking cognizance of workers as reflected in the Labour Act,” he said.

A jobs deficit has made it an employer’s market in Nigeria, leaving workers virtually powerless to negotiate – let alone demand – better terms.

Young and exploited

While Nigeria has rules that govern working conditions for full-time staff, the law does not specifically address “triangular employment’’ that covers workers hired through employment agencies.

‘’From the legal perspective, there is nothing illegal about having contract staff; it is a function of contract,” said Waleey Fatai, a Lagos-based labour lawyer.

“From the moral perspective, [it is an issue of] half a loaf is better than none,” he told Al Jazeera.

NUBIFIE’s Muhammed says the problem is not how the current laws are worded, but that employment agencies are falling afoul of it.

“The Labour Act that regulates the relationship did not exempt you because you are a secondary provider of employment,” he said. “It is part of the things we capture in this memorandum of agreement we just worked on.”

But not all contract workers may even be aware of their rights. Many employment agencies look for entry-level candidates in their early 20s with an Ordinary National Diploma (OND), the lowest tertiary degree in Nigeria awarded by polytechnics after a two-year programme.

A higher degree may even work against a job applicant.

Thirty-eight-year-old Ukamaka Olisakwe worked in two banks as a contract staffer between 2008 and 2014 in Nigeria’s east.

She told Al Jazeera the first bank that employed her told her to list her OND on her application but omit her more prestigious Higher National Diploma (HND) – a four-year degree that equates with a bachelor’s degree.

‘’I think they found a loophole in the academic system,” Olisakwe told Al Jazeera.

She said her first bank paid her a meagre base salary of N25,000 a month [$61] plus commission, and assigned to her work in the sales department where she was given performance targets including opening five to six new accounts daily, and generating monthly cash deposits often totalling millions of naira.

“The target heaped on the back of the workers was nasty, unbelievable, [and] mind-bending and if you are unable to meet [the performance targets], you won’t get your commission,’’ she said.

Olisakwe left that job and took a contract position with another bank where she worked in the customer service office alongside full-time, core staff.

‘’It is the same job function that I was doing with the core staff, only that I could not approve account openings,’’ she said.

But her odds of gaining an equal footing with the full-timers were slim.

In order to parlay a contract job into a full-time staff position, workers must take a conversion exam. But few are invited to take the test.

‘’Conversion rarely happens. They will only hand-pick some people,” she said.

Olisakwe finally quit the sector, worried that even if she did manage to convert a contract job into a full-time position, she would eventually fall victim to age discrimination.

“You know polytechnics churn young people every year and when they come for training, the banks retain them to replace the older staff,” she said. “It is cheaper.’

![]()