By Blaise Udunze

Between 2010 and 2026, a staggering $214 billion, approximately N300 trillion in public funds, has been reported as missing, unaccounted for, diverted, unrecovered, irregularly spent, or trapped in non-transparent fiscal structures across Nigeria’s public institutions.

That figure is not speculative but a conservative estimate of unaccounted funds. It is drawn from audit reports, legislative probes, civil society litigation, executive directives, and investigative findings spanning more than a decade. If it is to go by the accurate figure, the true national loss is likely higher but difficult to quantify precisely due to data gaps, overlapping figures, and incomplete audits.

The challenge is that in many of the most prominent cases, prosecutions have stalled, hearings have dragged without resolution, investigations have gone cold, and no defining jail terms have etched accountability into Nigeria’s institutional memory. The irony is that the number is historic, the silence is louder. And the economic damage is cumulative.

The pattern stretches from the oil sector to social investment programmes, from the Nigeria Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) interventions to ministry-level expenditures. In 2014, between $10.8 billion and $20 billion in unremitted oil revenues linked to the Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation triggered national outrage. Under the then CBN governor, Lamido Sanusi, who warned that persistent oil revenue leakages were making exchange rate stability “extremely difficult.” He cautioned that without full remittances, the alternative would be currency devaluation and financial instability. This concern spans the 2010 to 2013 oil revenue period. That warning proved prophetic.

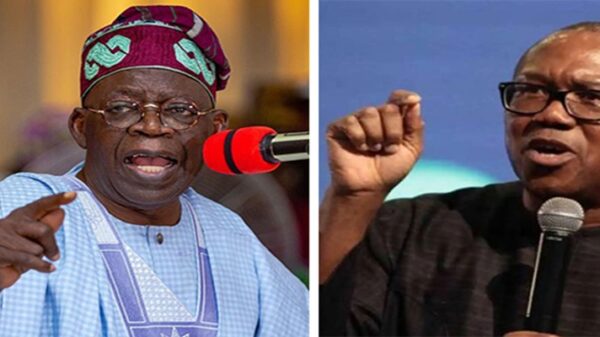

This is because, years later, the lack of transparency in the oil industry did not disappear, but rather it festered like cancer. It further led to the elongated audit queries, which have continued to trail the Nigerian National Petroleum Company Limited, including unremitted revenues, questioned deductions, and management fee structures under the Petroleum Industry Act. With an extraordinary move aimed at blocking revenue leakages at source, President Bola Ahmed Tinubu has recently issued an Executive Order suspending certain deductions and directing direct remittance of taxes, royalties, and profit oil into the Federation Account, which involves the reassessment of NNPC’s 30 per cent management fee and 30 per cent frontier exploration deduction under the Petroleum Industry Act.

Such presidential intervention underscores the scale of concern, which means that Nigeria cannot afford a structural lack of transparency in its most strategic revenue sector. But oil is only one chapter.

The Central Bank of Nigeria has faced some of the most far-reaching audit alarms in recent years. In suit number FHC/ABJ/CS/250/2026, the Socio-Economic Rights and Accountability Project (SERAP) is asking the Federal High Court to compel the CBN to account for N3 trillion in allegedly missing or diverted public funds. The Auditor-General’s 2025 report cited failures to remit over N1.44 trillion in operating surplus to the Consolidated Revenue Fund, over N629 billion paid to “unknown beneficiaries” under the Anchor Borrowers’ Programme, and more than N784 billion in overdue, unrecovered intervention loans.

There were also N125 billion in questioned intervention expenditures, irregular contract variations exceeding N9 billion, and procurement gaps running into hundreds of billions. The Auditor-General repeatedly recommended recovery and remittance. No date has been fixed for the hearing. Meanwhile, Nigeria continues to borrow.

Elsewhere, the House of Representatives has launched a probe into over N30 billion recovered during investigations into the National Social Investment Programme Agency (NSIPA). The funds, reportedly frozen during investigation, have not been remitted back into the Treasury Single Account, stalling poverty-alleviation schemes like TraderMoni and FarmerMoni. Millions of vulnerable Nigerians remain exposed while lawmakers search for money already “recovered.” The irony is staggering as funds are found, but programmes remain frozen.

A top discovery recently that put the nation on red alert was made by the Senate committee, which claimed to have found N210 trillion in financial irregularities in NNPC accounts between 2017 and 2023, including unaccounted receivables and accrued expenses. A critical concern is that, as of early 2026, this has sparked commentary but no clear prosecutions.

Only recently, in the power sector, SERAP has urged the President to probe alleged missing or unaccounted N128 billion at the Federal Ministry of Power and the Nigerian Bulk Electricity Trading Plc. Of concern is that despite the enormous funds channeled in this sector, Nigeria’s chronic electricity instability persists, even as billions meant to stabilise the grid face audit scrutiny.

Across MDAs, audit reports between 2017 and 2022 flagged trillions in unsupported expenditures, unremitted taxes, unauthorized payments, and statutory liabilities never recovered. These sums are dizzying and are also alarming; N300 billion here, N149 billion there, N3.403 trillion across agencies, N30 trillion-plus Treasury discrepancies raised at the Senate level.

Individually, they shock. Collectively, they define a structural pattern. And patterns shape economies.

Nigeria operates with structural fiscal deficits and also lives with them routinely and comfortably. Expenditure persistently exceeds revenue. When public funds disappear, fail to be remitted, or are trapped outside constitutional channels, the deficit widens. The government must borrow to fill gaps created not only by low revenue, but by revenue leakage.

Debt servicing now consumes a disproportionate share of federal revenue. Borrowing meant for capital projects increasingly finances recurrent obligations. The country shifts from borrowing to build to borrowing to survive. Every missing naira compounds tomorrow’s liability.

The Treasury Single Account (TSA) was designed to plug such leakages. It consolidated government revenues under Section 80 of the Constitution into a unified framework. International financial institutions commended it as a landmark reform. Yet even today, the Minister of Finance, Wale Edun, has admitted that substantial government funds remain outside the TSA and outside the CBN’s consolidated visibility. Until August 1, 2024, he revealed, the federal government could not fully see its own balance sheet at the apex bank. That admission should alarm any serious economy.

Fiscal lack of transparency constrains planning. It undermines monetary coordination. It weakens debt sustainability projections. It distorts policy responses. And when systems are in flux, money vanishes more easily.

Changing or weakening the TSA in such an environment would be catastrophic. Transitions create windows of vulnerability. Old accounts close. New accounts open. Reconciliation’s lag. Ghost contractors reappear. Double payments slip through.

Albeit, the government must learn to tread with caution as Nigeria’s institutional bandwidth is already strained by simultaneous tax reforms, exchange-rate adjustments, subsidy removal, and fiscal restructuring. One truth that cannot be argued is that layering additional structural upheaval onto fragile systems risks revenue loss that the country cannot afford. Investors are watching.

Credit markets evaluate not just numbers but institutional consistency. A nation that abandons or weakens its most credible fiscal reform sends a destabilising signal. Stability lowers borrowing costs. Institutional drift raises them. But beyond markets lies the human cost.

N300 trillion represents roads not built, power plants not completed, irrigation systems not funded, schools not modernised, and hospitals not equipped. It represents jobs not created and industries not catalysed. It represents stalled productivity and deferred growth.

When intervention loans remain unrecovered, agricultural output suffers. When power sector funds are unaccounted for, electricity remains unstable. When social investment funds are frozen, poverty deepens.

Inflation then compounds the pain. Revenue gaps push borrowing. Borrowing pressures interest rates and by extension, liquidity misalignment fuels price instability. Citizens pay through higher food costs, transport fares, and rent. The poor pay first. The middle class erodes quietly.

Perhaps most corrosive is the trust deficit. When audit queries fade without visible accountability, tax morale weakens. Compliance declines. Cynicism hardens. A nation cannot modernise where trust in fiscal integrity is fragile.

Section 15(5) of the Constitution requires the abolition of corrupt practices. Financial Regulations mandate a surcharge and referral to anti-corruption agencies where public officers fail to account for funds. The Fiscal Responsibility Act empowers citizens to enforce compliance to ensure that government officials follow fiscal rules. But enforcement defines seriousness.

Nigeria’s problem is not a lack of audit findings. It is the distance between findings and finality.

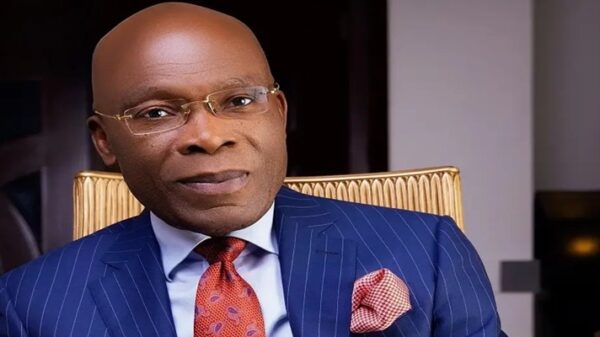

Nations do not collapse overnight due to a lack of funds. They drift. Infrastructure decays incrementally. Debt rises gradually. Growth slows subtly. Confidence erodes quietly. Then one day, stagnation feels permanent. $214 billion (N300 trillion), sixteen years of recurring audit alarms. Few conclusive accountability outcomes are proportionate to the scale. Truly, the consequences have been less strong. For the same reason, the country witnessed President Tinubu nominating ex-NIA boss Ayodele Oke as ambassador despite a $43 million loot in an Ikoyi apartment.

See the research breakdown of some of the audit figures that reveal staggering sums as enumerated above:

– $10.8 billion and separately $20 billion in unaccounted oil revenues at the NNPC in 2014

– $1.1 billion controversial Malabu Oil and Gas oil deal in 2015

– $2.2 billion arms procurement irregularities in 2015

– N3.4 billion from IMF COVID-19 financing flagged in a 2020 audit.

– N149.36 billion, N37.2 billion, and multiple irregular MDA expenditures in 2020 alone.

– N300 billion cited in public audit concerns in 2017.

– N210 trillion in financial irregularities uncovered, N103 trillion in ‘accrued expenses’, and another N107 trillion in unaccounted ‘receivables’ (2017 -2023).

– N57 billion Ministry of Humanitarian Affairs – (2021)

– N3 trillion and N1.44 trillion flagged in 2022 audit issues involving the Central Bank of Nigeria.

– Nearly N630 billion under the Anchor Borrowers Programme is reportedly unrecovered.

– N784 billion in overdue intervention loans flagged.

– Over N3.403 trillion unaccounted for across federal MDAs between 2019 and 2021.

– Roughly 30 trillion+ in Treasury Single Account and Consolidated Revenue Fund discrepancies raised at the Senate level.

– N500 billion in unremitted oil revenues between 2019 and 2024.

– N80 billion tied to alleged fictitious contracts in the Accountant-General’s office.

– N69.9 billion in uncollected statutory tax liabilities.

– Billions more in unauthorized or undocumented expenditures across ministries.

The institutions differ. The years differ. The audit language differs. The pattern does not.

Nigeria’s economic future will not be determined solely by how much oil it produces, how many reforms it announces, or how many executive orders it signs. It will be determined by whether every naira earned enters the Federation Account transparently, whether every intervention loan is tracked and recovered, whether every surplus is remitted constitutionally, and whether every diversion carries consequences. Revenue generation matters. Revenue protection is destiny. Because when government funds go missing, nations do not stand still. They move backwards.

Blaise, a journalist and PR professional, writes from Lagos and can be reached via: [email protected]

![]()